Please enjoy this encore from the Sleeps With Monsters archives, first published February 4, 2014.

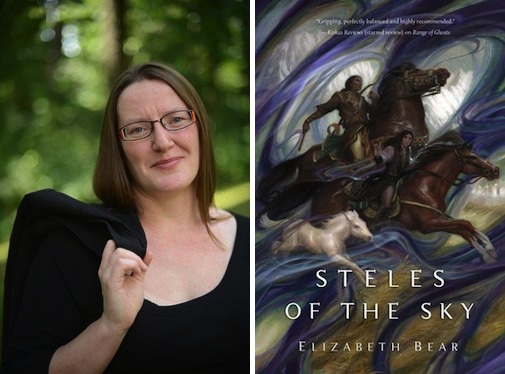

Today we’re joined by the amazing Elizabeth Bear, who has graciously agreed to answer some questions. Bear is the author of over twenty novels and more short fiction than I dare to count—some of which is available in her collections The Chains That You Refuse (Night Shade Books, 2006), and Shoggoths in Bloom (Prime, 2013). She’s a winner of the 2005 John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer, and Hugo Awards in 2008 and 2009 for her short story “Tideline” and the novelette “Shoggoths in Bloom,” among other accolades.

Many of her novels feature highly in my list of all-time favourites (and I’m really looking forward to her next one due, Steles of the Sky) so I’m thrilled to be able to interrogate her here today. Without further ado, then, let’s get to the questions!

LB: Let me start somewhat generally, by asking you your opinion of how women—as authors, as characters, or as fans and commenters—are received within the SFF genre community.

EB: That is, in fact, a general question—a question so general that for me, at least, it’s unanswerable.

The genre community is not in any way a monolithic thing. Women within it—in any of those roles—are not monolithic. The Venn diagram comprised of these two overlapping sets—the genre community and women within it—is comprised of people. Different people, with different ethnic and racial identities, different religious and political backgrounds, different life and family experiences, who grew up surrounded by different experiences relating to time, place, and culture. And the ones who identify as women have different personal experiences of what being a “woman” is.

There are definitely challenges in being a woman in the genre community that men may not face—but no single segment of that community is comprised of a unified and undifferentiated mass of Being Problematic About Girls.

I suspect a certain number of our troubles as a community come from a tendency to see parts of the spectrum that we do not identify with as unified and undifferentiated and unpersoned mass—the tendency of people in groups, as George Carlin put it, to choose up sides and wear armbands.

It’s easy to other people, to assign them to faceless groups. Or to assign ourselves to cliques, for that matter.

LB: You’ve written in a wide variety of subgenres, and a wide variety of kinds of stories—from the cyberpunk future of Hammered to the Elizabethan secret history of Hell and Earth, and from Dust’s generation-ship posthumanism to the Central-Asia-inspired epic fantasy of Range of Ghosts—and in both novels and short fiction. Would you like to talk a little bit about this variety and how it reflects your vision—if I can use that word—for the genres of the fantastic?

EB: I have no idea how to answer the question about “vision.” I have no particular vision for the genres of the fantastic, as you put it. I don’t see it as my place in the world to control or manage what other people write. I’ve occasionally written a tongue-in-cheek manifesto or two about something I thought was problematic, and I’m very invested in encouraging the growth of diversity in the field and the Rainbow Age of Science Fiction.

I write a lot of different things because I read a lot of different things. I write what I love, what I have read since I was big enough to hold a book. I guess that’s the only real answer.

I might have a more financially rewarding career if I had stuck to near-future SF thrillers… but I would have a much less personally rewarding one.

LB: You write what you love. So what is it about SFF across all the subgenres and long and short forms that speaks to you?

EB: At its best, SFF is willing to break things, to test things, not to take anything for granted—social structures, the laws of physics, even what it means to be a human being. It’s about asking questions that have no definitive answers, about stretching the definition of the possible, and that’s what I love it for.

I’ve referred to it as the literature not of ideas, but of testing ideas to destruction—and at its best, I think that’s absolutely true.

LB: So what ideas have you been testing to destruction with the Eternal Sky trilogy?

EB: Oh, now you want me to do everybody’s homework for them! Also, cutting something that neatly clean in terms of reasons is rarely possible for me. I can tell you some of my goals and the arguments I was having with the genre and myself, however.

I wanted to examine some of the base tropes of Western epic fantasy, especially regarding who the default protagonist and what the default cultures are—and who the default villains are.

It was also written in some ways because I feel like we as a genre have been writing in reaction to the heroic tradition without really necessarily integrating that reaction as well as we might. I wanted to write a story for one of my best friends, who is of Indian descent and wanted to see more SFF set in Asia, and not just societies loosely modeled on Japan and China. And I was tired to death of the roles available to women in epic fantasy being far more limited than the roles available to women historically. I was tired of fantasy worlds where there’s no history and no technological or social progress, but somehow it stays 1100 for a thousand years.

I also wanted to talk about worldviews and I wanted to talk about some of the assumptions of cultural relativism, and how worldview actually shapes what we perceive to be real.

Also, it seemed like it would be a lot of fun. It’s a world I’ve been working on since the 1990s; I thought it was time to show some of the breadth of that tapestry.

LB: Can you expand on what you mean by “writing in reaction to the heroic tradition without really necessarily integrating that reaction as well as we might”?

EB: We have a tendency as a genre, and I include myself in this, of course, to jump from one extreme from the other without exploring the intersections between those extremes. It’s a dichotomy John Gardner described as “Pollyanna” vs. “disPollyanna” attitudes, and as he points out, both of these extremes are facile and uninteresting. Nihilism is awfully attractive to people who want to feel deep without actually accepting any responsibility for fixing things that are shitty.

Also, our criticism of existing works is often more interested in rhetorical flourishes and fairly flat analyses than in a nuanced understanding of the text. As a more concrete example, anybody who dismisses Tolkien as a one-dimensional apologist for monarchism is reading their own preconceptions, not the text. Likewise, anyone who dismisses an entire subgenre as exclusively X or Y—“Steampunk is all colonial apologism and glorification!” is not actually engaging with a significant percentage of existing literature—especially that written by people of color and women, and—for that matter—women of color.

I’ve got no time for that.

LB: Can you expand on what you mean by “how worldview actually shapes what we perceive to be real” in reference to the Eternal Sky trilogy?

EB: Actually… no, I’m not sure I can expand on that. Worldview shapes what we perceive to be real. I’m not sure how else to express it.

LB: What books or writers have had the most impact or influence on you as a writer? And why?

EB: I’m not sure any writer is actually qualified to answer that question. Influences are heavily subconscious; it happens fairly frequently that I’ll be reading the work of a long-time favorite and stumble across an idiosyncratic sentence construction that I also use, and realize that’s where I got it from. I read a lot. I always have. But I’m not sure I’m writing in the mode of anybody, exactly.

Maybe a bit of Zelazny and a bit of Russ show through here and there.

I could tell you what my favorite books are, or the authors I wish I could emulate, but those are boring answers.

You’ll have to ask the scholars in fifty years or so. And they’ll probably disagree.

LB: Final question. What are you working on now? What should we expect to see from you in the near- and medium-term future?

EB: Currently I’m working on a wild west Steampunk novel called Karen Memory, which is coming out from Tor in 2015. It involves heroic saloon girls, massive conspiracies, and at least one fascinating and oft-ignored historical character.

I’ve delivered the final book of the Eternal Sky trilogy, which is central Asian epic fantasy, and that should be out in April.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. Her blog. Her Twitter.